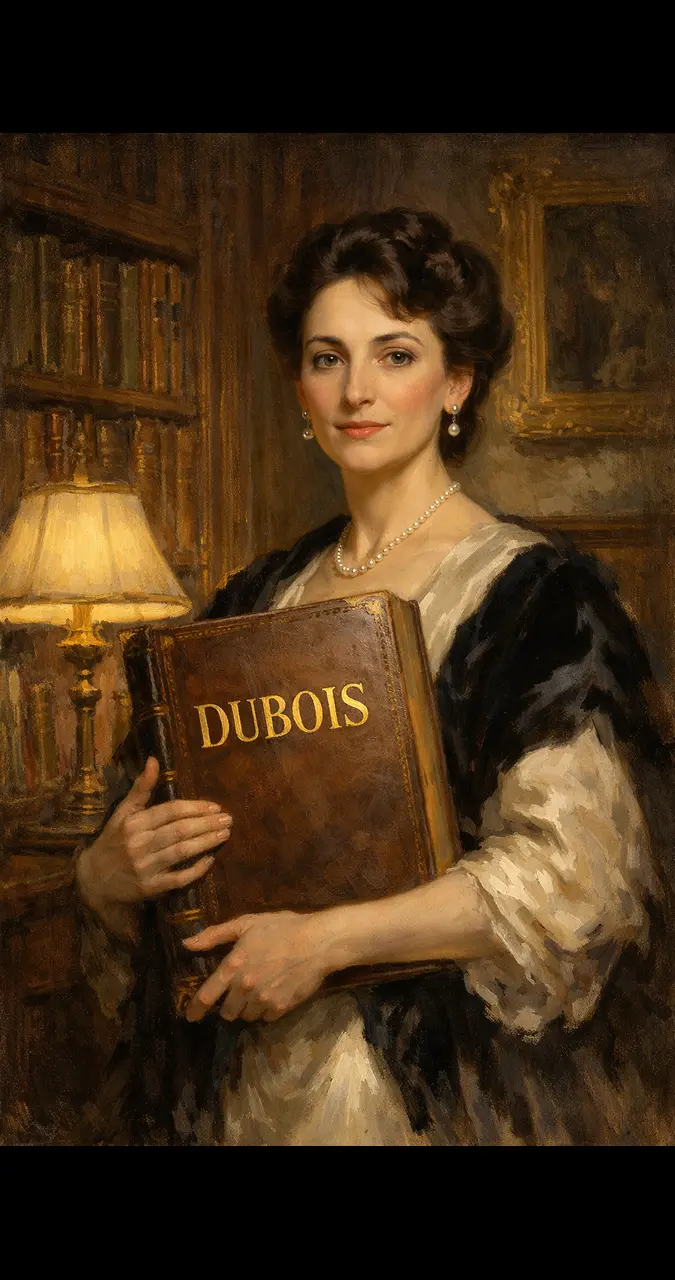

deborah dubois deborah dubois

In modern architecture and design, few individuals have Dubois’s weight, insight, and soft power. While other starchitects are noted for their headline-grabbing, outrageous high-rises, Dubois steadily and quietly built her claim to be the foremost contemporary advocate of the human-centered, sustainable design of her choosing. It is about much more than the carbon footprint. It is a positive fusion of ecological and social healing with beauty. It is about integrating the community’s positive social ecology. This is the story of how Dubois transitioned into and changed the mainstream of the architectural profession.

The Formative Years: Seeds of a Philosophy

Dubois’ ethos was formed not by a high-end design school but by the high-end, dense, and splendid rainforests, coupled with the simple and beautiful villages of Southeast Asia and the West African vernacular, which were the sites of her early professional travels. Dubois, the daughter of a cultural anthropologist, understood early on that the best and most effective design is local. She also understood that integrating social, vernacular, and architectural systems, such as community well-being as a social focal point and architectural elements aligned for passive cooling, was key.

“I didn’t see ‘buildings’,” recounts Deborah Dubois from one of her original interviews. “I saw living, breathing extensions of the people and the land. That lesson—that design must serve and belong—became my non-negotiable first principle.” This principle would later clash with, and ultimately transform, the stark modernism she encountered during her formal education at Ivy League institutions, where she was often the sole advocate for such an approach.

Dubois Doctrine: Principles Over Projects

What truly defines Deborah Dubois is not a single famous skyscraper, but a design doctrine that is solid and replicable. Dubois Studio, her design firm, is a laboratory for these doctrines. Their design principles can be distilled into three main pillars:

Biophilic Integration: Deborah Dubois views and defines sustainability in sensory terms. It is more than just solar panels on a roof; it is an assurance that every occupant feels a day-to-day connection with the natural ecosystem. Her designs are exemplars of biophilic design: Humidifying and soothing interior water features, thoughtful “light shelves” that pour light deep into the area of a building and bounce sunlight 30 feet, ventilation systems that mimic termite mounds and even eliminate the need for AC. Green space is structurally integrated and is never an afterthought.

The Community as Co-Designer: The most radical characteristic of Dubois’ approach is her participatory design. Before Dubois and her team draw any lines, they embed themselves in the community that will use the space. For the now-famous “Havenhill Community Hub,” workshops were conducted in town halls, schools, and even local pubs. The final structure, which includes a marketplace for local artisans and multi-generational activity zones, was shaped by the direct input of hundreds of community members. “The architect is not a deity delivering a masterpiece. We are translators and synthesizers of collective need and dream,” Dubois argues.

Material Kinship: D. Dubois buildings honor and tell the geological and cultural story of their locations. Dubois led the use of contemporary, regionally sourced, low-embodied-carbon materials long before it became a trend. A library in New Mexico features beautifully crafted rammed-earth wall patterns. A coastal retreat in Maine features reclaimed fishing boat beams. This “material kinship” eliminates the need for long-distance transport of materials, reduces emissions, supports local economies, and creates buildings that feel rooted to their location.

Signature Projects: Philosophy in Concrete and Green

Her philosophy is universal, but the application is specifically brilliant. Two projects succinctly capture the essence of the D. Dubois vision.

The Sentinel School (Portland, Oregon): However, Deborah Dubois was allowed to design an elementary school, and instead of using this model, she created The Sentinel School without using the standard, prison-like model.’ Acceptance of the Sentinel School as a net-positive energy campus means it produces 20% more energy than it consumes, and serves as a model for other campuses. Classrooms that open directly to wetlands and school edible gardens that are part of the school’s wetland science program. Children learn and play on a sloping rooftop meadow, with a raised grassy area. Metrics on academic performance and student well-being showed almost immediate improvement, providing empirical evidence that her human-centered design approach benefits schools and students.

The Resilio Towers (Singapore): This project demonstrated that the Deborah Dubois doctrine could extend to vertical construction. Resilio Towers are a pair of glass towers in a city of glass giants, and are a breath of fresh air. Sky forests are designed to offer vertical biodiversity and are linked at multiple levels to promote it. Every residential unit is outfitted with a proprietary passive wind-capture system engineered to cool and circulate air. Resilio Towers was a landmark project that illustrated how hyper-density and ecologically sustainable design could coexist. It won the Global Sustainable Design Award and silenced critics of her work.

The Legacy and the Future: Nurturing Future Generations

The legacy of Deborah Dubois extends beyond the boundaries of any studio. She is an educator and a professor who guides a fresh cohort of architects. Her “Design for Belonging” program is being implemented in universities around the globe. “The challenge ahead isn’t technological,” she tells her students. “We have the tools. The challenge is philosophical. We must redesign our relationship with the planet— from one of extraction to one of reciprocity.”

Deborah Dubois’s legacy is a transformed and reshaped landscape. She relocated the notion of sustainability from a technical checklist to one that is profoundly ethical and deeply aesthetic. Success in her eyes was not a profit margin or the height of a building, but rather social cohesion, environmental renewal, and the quiet happiness of the occupants.

Conclusion: More Than a Name

Ultimately, Deborah Dubois is not just a person, but a brand that is becoming synonymous with a new type of construction, a brand with a new level of integrity, a new baseline for contemporary design. In times of global challenges, Deborah Dubois’s work serves as a design for enduring hope. Her buildings effectively demonstrate that a constructed world is possible, one that, instead of merely consuming resources, also regenerates them. It shows that the built environment does not need to segregate individuals, but can support and cultivate a community. The world is not just a better place because of her designs, but is a more beautiful, more sustainable place, and she is doing it one building at a time. Deborah Dubois, the unseen architect, has provided society a legacy that embodies the vision of design with a conscience.

you may also read nowitstrend.